In Reading Lessons, I write about the shadow colleagues who share my classroom and help with my lessons: the novelists and poets and playwrights without whom I couldn’t do my job. This week, with Year Eight, it’s been Seamus Heaney. Lovely Seamus: I think he’d have been a good person to work with, slightly irreverent but also deeply wise, with a well-honed sense of the difference between the things worth cherishing and the merely faddish. He’d have a secret biscuit stash, too.

We’ve been teaching Year Eight about close reading, Seamus and me. Our Year Eight poetry unit – now in about its tenth iteration – is called ‘Mysterious Beasts’, and focuses on poems about different creatures. We explore William Blake’s ‘The Tyger’, Ted Hughes’s ‘Pike’, and U.A. Fanthorpe’s ‘Not My Best Side’, alongside a number of poems from Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris’s beautiful book The Lost Words. And we write our own poems, experimenting with diction and form, making careful choices of language. Before Christmas, we wrote a haiku about a pangolin, trying to find the exact way of conveying its pineconey strangeness. You can’t waste words with a haiku; they’re brilliant for developing precision.

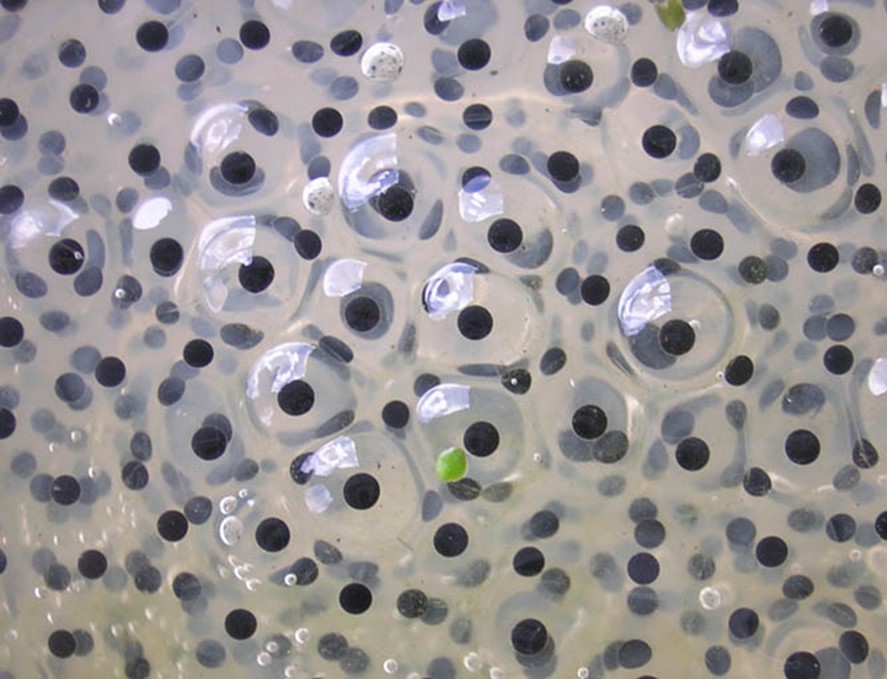

This week, we looked at Heaney’s poem ‘Death of a Naturalist’. It’s been the first week back after Christmas, so we eased ourselves in with a wordcloud that allowed us to explore some of the key vocabulary in the poem. We noticed the rhyme of ‘clotted’ and ‘rotted’, and the onomatopoeic ‘slap’ and ‘plop’. We used dictionaries to find the precise meanings of ‘obscene’ and ‘coarse’, and talked about the fact that ‘coarse’ can be both literal – a prickly item of clothing, a hessian sack – and metaphorical. We talked, above all, about unpleasantness: about smells and textures and associations. We said words out loud. Slap. Slime. Spawn. Say them, and draw out the ‘s’ sounds: there’s something there to luxuriate in, to enjoy.

This gives us a neat springboard to talk about how often, as children, we relish exploring things that would make our older selves squirm. The boys share stories of digging up worms, playing in mud, squishing up their food and making shapes with it. Before they’ve even seen the complete poem, they’ve started to inhabit the sensory world that Heaney creates in it, and from this point, it’s just a short jump to the flax-dam in the townland, sweltering in the heat of the sun.

We listen to Heaney reading the poem out loud, because it’s best in his voice. Here he is: give him a listen. We listen twice, and try to identify the story he is telling. The first part of the poem is relatively simple, the boys decide. It’s a little boy who collects frogspawn, and is fascinated by it. He fills jam-jars full of it and watches as the tadpoles hatch. But then, in the second part of the poem, something changes. There’s a threat, a fear. The boy is surrounded by frogs and feels their anger. There is something disgusting about them that wasn’t there before. They are an army, intent on revenge. We talk about what has happened. They want vengeance, one boy volunteers, because the narrator stole their children and abandoned them, and it’s a perfect summing-up of what Heaney describes.

This is one of my favourite poems to teach, and this Year Eight group is one of my favourite classes. They’re sparky, full of ideas, but biddable. We have routines. Countdowns from three and then silence. If I stand at the front of the room with my hands on my head, they have to stop what they’re doing and put their hands on their heads, too. They like the predictability of it. They like lots of positive framing – well done to all those people who’ve put the heading and date and underlined it neatly – and rewards. And they like to discuss. One of my PGCE lecturers, back in the mid-90s, talked about students as being divided into ‘oopidoops’ and ‘begetters’. The oopidoops were the lively ones, like shaken bottles of lemonade, needing to be channelled and directed. The begetters would just be getting on with what they were supposed to be doing. This class is about half and half. I have a fantastic TA who is brilliant at spotting when someone needs a fidget toy, a resistance band for some sensory input, a quiet moment outside. He’s also brilliant at suggesting alternative interpretations and offering thoughts. We bounce ideas off each other and enable the students to see that in English, there are shades of meaning waiting to be explored, ambiguities that don’t need to be resolved and closed down. It’s okay to hold multiple possibilities in your mind.

It’s a double lesson, and we need a movement break by now. An hour and forty minutes is a long time to sit, when you’re twelve. We stand up. A necessary stretch; some shoulder rolls and finger wiggles. Some jumps and hops to discharge some of that oopidoop energy. Then some smaller movements, borrowed from my Pilates instructor, to get them focused and concentrating again: sway into your toes and then into your heels, without taking your feet off the floor, and do this slowly, breathing in as you go forwards and out as you go back. Two minutes and we’re working again. We’re looking more closely at Heaney’s descriptions now, and at how he blends pleasure and disgust. We examine how he builds the setting, and relate this to the ditches and streams that the boys know, what they smell like in summer when they’re thick with vegetation. We discuss the precise meaning of ‘sweltered’, the stickiness and discomfort. We explore the contradictoriness of ‘gargled delicately’, and I introduce the term ‘oxymoron’, easing the vocabulary in where it’s needed rather than teaching it in isolation.

I ask the boys their favourite line. ‘But best of all was the warm, thick slobber of frogspawn’ is the overall winner. They love the sensoriness of it, that childlike delight – best of all – in the warmth and ooze. They love the word ‘slobber’, and say it, just like ‘spawn’ and ‘slime’. They listen to each other, and build, consciously, on each other’s contributions. When they write their ideas down, they’ve got lots to say. Sometimes, they need a bit of help shaping it. ‘I know what I want to say, but I’m not sure how to say it’, one boy tells me. I ask him what he wants to say, and it’s perfect. ‘So can I just write that down?’ he asks. I reassure him that yes, he can, and he’s off, pen whizzing across the page.

I could do all of this in a very different way. I could stand at the front and tell them, line by line, what the poem means. They could copy down my annotations and then write a perfectly-scaffolded paragraph. But the poem would stand apart from them, somehow. As it is, they’ve inhabited it. They’ve explored it, stage by stage, peeling back layers, making connections. This isn’t child-led ‘discovery learning’. It’s carefully structured and relies on a deep understanding of both the poem and the class. It’s a lot harder than lecturing from the front would be. It certainly requires more energy, more presence in the room, more of a sense of who’s thinking what: whose ideas to draw out a little bit further, who to ask next, who needs a bit of help to articulate what they’re thinking. By the end, I need to sit down somewhere quiet.

But this energy is what makes it all worthwhile. Years ago, Richard Jacobs described English teachers as like lightning conductors for the relationship between the text and the student, and that’s what teaching this particular class is like. We had a good time, Seamus and my TA and Year Eight and me, and it reminded me why I like my job so much.